The AI We Actually Need Isn’t an Exam Machine

The progress of large language models over the past few years has been genuinely impressive.

They can solve International Math Olympiad problems, write complex code, and pass all kinds of professional exams.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: these capabilities aren’t what most people actually need.

Think about how you actually work.

A programmer gets a new tool’s documentation and starts debugging right away. A gamer picks up a new rulebook and learns as they play. A scientist stares at experimental data and discovers new patterns.

These scenarios share one thing in common: we’re not recalling knowledge learned years ago — we’re learning in real-time from information right in front of us.

Tencent’s Hunyuan team gave this ability a name: Context Learning.

And their research found that today’s most powerful AI performs abysmally at it.

What Is Context Learning?

Let’s clarify the concept.

Current LLMs derive their core capabilities from pre-training. Simply put, during training, massive knowledge gets “compressed” into model parameters. During inference, models primarily rely on “recalling” this static internal memory to answer questions.

This creates a structural contradiction.

We’ve optimized models to be experts at “reasoning from known knowledge,” but what users actually need is models that can handle messy, constantly changing, completely new contextual information.

A few real examples:

- Given a 70,000-word drone SDK document, convert natural language flight instructions into compliant code

- Given a 15,000-word new game rulebook, analyze all possible endings for an escape room scenario

- Given 300 raw experiment logs, derive underlying physical relationships and estimate resonance constants

These tasks can’t be solved by “things the model already knows” — they require learning on the fly from given context.

That’s the core meaning of Context Learning.

CL-bench: An Exam Designed Specifically for This

To quantify current models’ context learning capabilities, Tencent Hunyuan built a benchmark called CL-bench.

It’s substantial: 500 complex contexts, 1,899 tasks, 31,607 verification criteria. All hand-annotated by experienced domain experts, averaging 20 hours per context.

The core design principle is singular: every task must require learning new knowledge from the context to solve.

Models can’t coast on pre-trained knowledge.

To ensure this, they employed three anti-contamination strategies:

First, fictional creation. Experts invented entirely new content. For example, designing a complete legal system for a fictional country, including precedents and legal principles. Or inventing a brand-new programming language with unique syntax and semantics.

Second, modifying real content. Creating variants based on real-world material. For instance, altering historical events, modifying scientific definitions, or reworking technical documentation.

Third, using obscure and cutting-edge content. Material that barely appeared in pre-training data, such as the latest research findings, newly released product manuals, or highly niche domain knowledge.

How effective was this? Without any context provided, the strongest model GPT-5.1 (High mode) could solve less than 1% of tasks. The data was indeed “clean.”

Four Testing Dimensions

CL-bench categorizes context learning into four types:

Domain knowledge reasoning. Given a specific domain’s knowledge system (like a fictional legal system or innovative financial instruments), you must use this knowledge to reason through and solve concrete problems.

Rule system application. Given a set of newly defined rules (like new game mechanics, mathematical formalisms, or programming syntax), you must understand these rules and execute tasks.

Procedural task execution. Given a complex procedural system (like workflows, product manuals, or operation guides), you must follow the procedures to complete tasks.

Empirical discovery and simulation. Given experimental data, observation records, or simulated environments, you must discover patterns and regularities. This is the hardest category because it requires inductive reasoning, not just deductive reasoning.

Additionally, 51.1% of tasks have sequential dependencies — later questions depend on earlier answers. This dramatically increases difficulty.

Results: Even the Best Model Only Gets 23% Right

Tencent tested 10 state-of-the-art large language models.

The results are brutal.

On average, models could only solve 17.2% of tasks. The best performer, GPT-5.1 (High mode), managed just 23.7%.

In other words, all the needed information is sitting right there in the context, and models simply can’t learn from it.

Several key findings:

The biggest failure mode: ignoring or misusing context. Many errors weren’t due to insufficient information — models ignored critical details in the context or used them incorrectly. More interestingly, models frequently “fell back” to assumptions from pre-training, even when the context explicitly defined new rules and concepts.

Long-context reasoning and instruction following are necessary but not sufficient. Even models that handle long texts and follow instructions well still fail at context learning. This suggests context learning is an independent capability, not merely the sum of these two abilities.

Inductive reasoning is far harder than deductive reasoning. On tasks requiring pattern discovery from data, many models had success rates below 10%, with high variance across runs. By contrast, tasks involving deduction from given rules fared somewhat better.

Increasing reasoning effort helps somewhat, but with limited effect. For instance, GPT-5.1 in high reasoning mode scored about 6% higher than in low reasoning mode. But some models actually performed worse with increased reasoning effort, suggesting that “thinking harder” alone doesn’t help — what matters is whether models can correctly absorb and organize contextual information.

Longer contexts are harder, but short contexts can be complex too. Length is indeed a bottleneck, but even short contexts can trip models up if they have high information density, subtle rules, or complex dependencies.

What Does This Mean?

This research helps explain a common frustration: why do models still drop the ball at critical moments, even when you’ve carefully crafted your prompts and context?

The answer: providing context isn’t enough if models fundamentally can’t learn to extract and apply information from it.

Context learning as a foundational capability has long been overlooked. Until this capability improves, LLMs will remain fragile in the scenarios where they’re needed most — messy, dynamic, real-world environments.

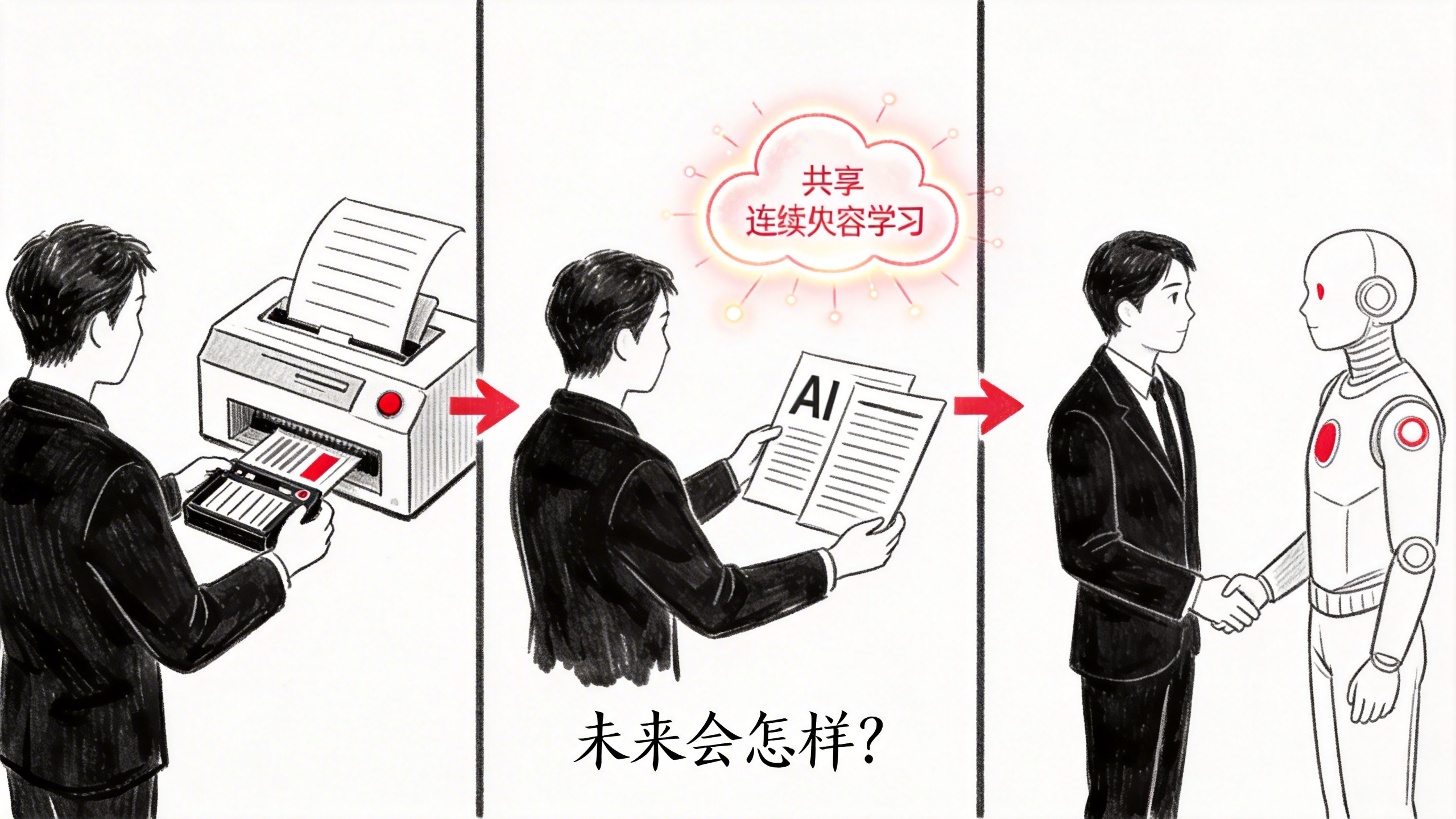

What Does the Future Hold?

Tencent’s team offers an intriguing vision.

If context learning capabilities improve dramatically, the relationship between humans and AI would undergo a fundamental shift: the human role would transform from training data provider to context provider.

No longer “I feed you data so you can learn,” but rather “I give you information about the current situation, and you learn on the fly.”

But there’s a deeper question: context learning is ephemeral. Whatever the model learns within the current window is forgotten once the window closes.

How do you turn context-learned knowledge into persistent memory? This isn’t just about remembering facts — it includes skills, experience, and patterns.

This may be the next major challenge to solve.

As the authors wrote in their conclusion: “It’s time to make context learning a reality.”