On February 5th, OpenAI and Anthropic released their new models on the same day — GPT-5.3-Codex and Claude Opus 4.6.

The timing itself is interesting. Both companies dropped their releases on the exact same day, which means they both knew the other was about to play their hand.

But what’s even more interesting is that the entire AI community’s discussion shifted after this launch.

Nobody’s excitedly sharing benchmark screenshots anymore. Nobody’s saying “Model X completely crushes everything.” Instead, everyone’s asking: how does it actually feel to use?

This shift is worth a deep dive.

The Bottom Line: Opus Is More Usable, Codex Is More Powerful

Nathan Lambert (author of Interconnects AI, an independent observer who closely tracks frontier models) has been using both models intensively. Here’s his experience:

Claude Opus 4.6 wins on “ease of use.”

Tell it “clean up this branch and push a PR,” and it understands the context and gets the job done. Try the same thing with Codex 5.3, and you have to guide it like a new employee — spelling out every step, otherwise it might skip files or put things in weird places.

Codex 5.3 wins on “ceiling.”

For complex code comprehension and bug fixing, Codex is genuinely a step above. Many of Nathan’s friends in the AI community rave about Codex, finding it capable of going that extra mile in high-difficulty scenarios.

But here’s the key issue: most people’s daily usage never touches that ceiling.

Codex 5.3’s Biggest Change: It Finally Doesn’t Feel Like “An OpenAI Model”

This sounds like an insult but is actually a compliment.

Previous Codex versions, including 5.2, had an infuriating problem — they’d constantly fumble basic operations like creating a new git branch. Can you imagine? A coding assistant that can’t even handle basic version control.

Codex 5.3’s biggest improvement isn’t a benchmark score increase — it’s that it finally caught up on product-market fit.

Nathan used a precise description: Codex 5.3 feels much more Claude-like. Faster feedback, broader task coverage, from git operations to data analysis, it can handle it all.

In other words, OpenAI finally realized that raw model capability alone isn’t enough. What users want is “hand you a task and you reliably get it done” — not “you scored two more points on some benchmark.”

But Both Models Share the Same Flaw

Nathan raised a very practical issue: whether it’s Opus 4.6 or Codex 5.3, when you assign them multiple tasks at once, they both develop “selective hearing” — dropping some instructions.

They perform best on well-scoped, clearly-bounded individual tasks.

This actually hints at something deeper: current AI coding assistants are fundamentally still “executors,” not “project managers.” You can’t dump a pile of tasks on them and go grab coffee. You need to act like a good tech lead — break tasks down and feed them one at a time.

Knowing how to manage AI is becoming a core skill.

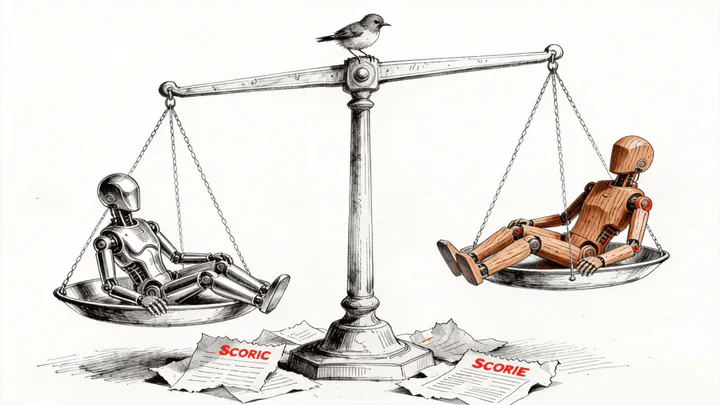

The Real Story: The Benchmark Era Is Over

This is the most important part of this article.

Think back to 2023-2025. Every time a new model launched, the first thing everyone checked was the benchmarks. GPT-4 launches — check benchmarks. Gemini launches — check benchmarks. o3 launches — still checking benchmarks. Back then, benchmarks genuinely mattered because the gaps between models were visible to the naked eye, and higher-scoring models actually performed better in practice.

But now it’s different.

Nathan says he barely looked at evaluation scores this time. He noticed Opus 4.6 scored a bit higher on search, and Codex 5.3 used slightly fewer tokens per response, but these numbers completely failed to tell him “which model is better to use.”

Why? Because the differences between models have shifted from “can it do this” to “does it feel smooth.”

It’s like evaluating two chefs — you can’t just compare who chops vegetables faster. You have to see whose food tastes better, whose kitchen is cleaner, and who better understands what you mean by “a little less salt.”

Gemini 3’s Lesson: Benchmark King, Irrelevant in Two Months

This example is too classic not to highlight.

In November 2025, Google released Gemini 3 Pro and the entire industry cheered “Google is back!” New York Times reporters were asking “Is Google about to reclaim the throne?”

The result? Two months later, in coding agents — the most critical battlefield — Gemini had virtually zero presence.

Benchmark leadership didn’t translate into product advantage. Users chose Claude and Codex in actual practice, and Gemini 3 became a “paper champion.”

What does this tell us? In the agentic era, the relationship between benchmark leadership and product leadership is much weaker than we assumed.

What Did Anthropic Get Right?

In retrospect, Anthropic’s strategic vision is genuinely impressive.

When Claude 4 launched in May 2025, Nathan himself admits he was skeptical of Anthropic’s bet on coding. Back then, OpenAI and Google were racing to see whose model could win IMO gold medals, whose benchmarks were higher — it was all very flashy.

Anthropic chose a path that looked less “glamorous”: focusing on perfecting the agentic experience.

They may not have been the only company to spot the agent trend, but they were the first to realign their entire company’s priorities around it. No benchmark chasing, no gimmicks — just making “pleasant to use” as good as it could possibly be.

Today, Claude Code has become the benchmark for coding agents. If you asked Nathan to recommend an AI coding tool to someone with little programming experience, he says he’d recommend Claude without hesitation.

At the dawn of the agentic era, user base is the ultimate moat. More users mean more usage data, more data means faster iteration — it’s a positive flywheel.

The Next Battlefield: Sub-Agents and “Agent Teams”

The article ends by pointing to an emerging direction: sub-agents.

Simply put, a primary agent can dispatch multiple “clones” to work on different parts of a problem simultaneously, then consolidate the results.

One comment section experiment was particularly fascinating: someone had 4 Opus 4.6 agents independently complete the same task with zero coordination, then had a 5th agent synthesize the results. The consolidated output was better than any single agent’s result, and the 4 agents had each developed completely different problem-solving approaches.

This kind of “emergent behavior” is something no benchmark can measure.

Claude currently leads slightly in sub-agent capabilities, but OpenAI has a unique advantage: the GPT-Pro series. When tasks become more complex and longer-running, the ability to throw more compute at a single problem becomes a key differentiator.

So, How Should We Choose Models in 2026?

Honestly, there’s no standard answer.

No simple table can tell you “use this model for X, use that model for Y.” You need to use multiple models simultaneously, switch flexibly based on task characteristics, and continuously track each model’s evolution.

This sounds like a hassle, but flip the perspective — it’s actually proof that AI tools have matured into a new phase.

Just as you wouldn’t use one knife for every dish, you shouldn’t rely on just one AI model. The real skill isn’t “picking the right model” — it’s “knowing when to use which model, and how to use it well.”

Someone in the comments said something I found spot-on:

Within a year, we probably won’t be comparing “models” anymore. The meaningful comparison will become: model + orchestration layer + tool access. Model capability itself is becoming table stakes.

I think they’re right. We’re moving from the “which model is stronger” era into the “whose system is better” era.

This shift is worth serious thought for everyone using AI tools.